Tragedy

Three days before she was due to stand trial accused of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice Eleanor de Freitas committed suicide. Last year she had accused a man1 of rape. The investigating officers believed her, but lacked sufficient evidence to prosecute him. The Metropolitan Police still categorise it as rape, but they told her that they did not think there was enough evidence to prosecute her alleged attacker.

De Freitas had mental health issues. She had previously been sectioned. She accepted the decision not to prosecute him. The man that she had accused did not. He decided that his only option to clear his name was a private prosecution against her. He gathered texts and CCTV for that purpose. This was the basis of the decision to prosecute de Freitas.

According to de Freitasʼ father the man harassed her with texts and voicemails. Unusually the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) decided to take over that prosecution. It insisted that the police provide a disclosure officer and claimed that new evidence surfaced, justifying prosecuting de Freitas. It also insists that there was new evidence that the police had not considered.

Last November Allison Saunders succeeded Sir Keir Starmer as Director of Public Prosecutors. Saunders provided a robust defence of the CPSʼ actions in this controversial and tragic case. Saunders insists that prosecuting de Freitas met both criteria – that there was sufficient evidence to offer a realistic prospect of conviction and that it was in the public interest. However, the CPS that she inherited operates in a culture of secrecy over how it reaches decisions on whether to prosecute or not.

Dark Ages

Previously the CPSʼ Code for Crown Prosecutors outlined the criteria that prosecutors needed to be aware of when making decisions on whether there was enough credible evidence to pass the realistic possibility of securing a conviction test. Back then the CPS was open about what the criteria were, although it stressed that these were only guidelines. It also defined what prosecutors should be aware of when deciding whether prosecuting was in the public interest or not.

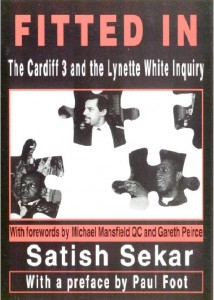

For further information on these criteria in an era when despite its faults – and there were many – the CPS believed in openness refer to Satish Sekarʼs book Fitted In: The Cardiff 3 and the Lynette White Inquiry2 at http://fittedin.org/fittedin/?page_id=15.

That Code meant that it was possible to compare the evidence relied on in a case to the requirements of the Code and judge whether it was right to prosecute or not. It also mandated its prosecutors to be aware of lines of defence and how that would impact on the possibility of securing a conviction. This plainly applied in de Freitasʼ case, but does that apply in the decision-making process any more?

The decision to prosecute de Freitas would surely have benefited from such openness on the decision-making process of the CPS. Crown Prosecutors may still apply the sufficiency test in the decision-making process, but without access to those criteria, how can the public judge the conduct of the CPS and how can they hold the CPS responsible for its decisions.

The previous Code would have meant that the decisions made in the de Freitas case could have been understood and assessed with access to the knowledge needed to make an informed decision. Instead, the public are left in the dark, depending on crumbs offered by the DPP. It could and should have been so different.

1 His name has been published elsewhere. However, we believe that rape is such an odious crime that a false accusation of that is more ruinous of the life of a wrongly accused person than in other offences and that consequently, a suspect accused of such an offence and denied the right to clear her/his name should at the very least be entitled to anonymity unless they waive such a right.

2 Chapter 4: Independent Eyes details ten of the 13 criteria and the evidence that the CPS had at its disposal at that time. That enabled the evidence it had to justify the prosecution to be compared to the guidelines contained in the Code. Any impartial and objective review of that particular prosecution should quickly see that the CPS failed its own test miserably.

Despite several requests for the CPS to explain its decision-making in that case the CPS has avoided doing so and it has also refused to register a complaint against it over this, let alone investigated the complaint for several years. Its conduct and that of the Attorney General’s Office has been shameful to put it mildly. These comparisons should have occurred in other cases. The criteria should be restored to the current Code for Crown Prosecutors in the interests of openness.