The End is Nigh

May 20, 2017

The Hardest Word

June 7, 2017By Satish Sekar © Satish Sekar (May 15th 2017)

Pitt’s Hypocritical Opportunism

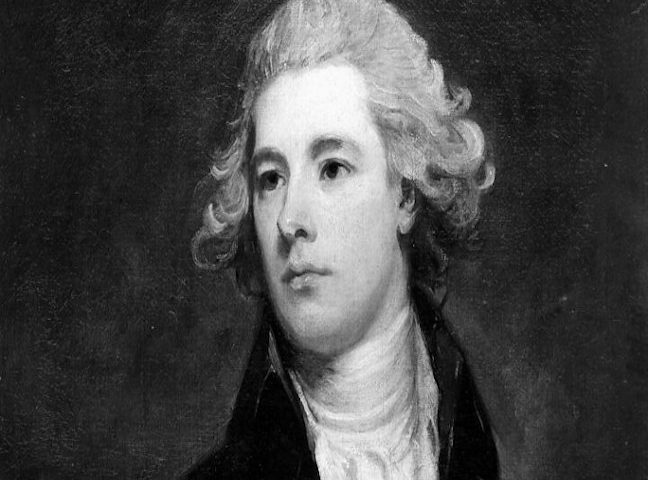

Toussaint Louverture adeptly played the colonial superpowers, France, Britain and Spain against each other, seeking the best arrangement, but his belief that independence was unnecessary ultimately cost him dear. Early in the Revolution, British Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, tried to exploit France’s difficulties by proposing legislation to abolish slavery, but William Wilburforce was soon stopped in his tracks as Pitt saw an opportunity to seize Haiti for Britain and deal a blow to France in the process.

Who cared if that would cost slaves their liberty for another 45 years? Pitt certainly didn’t. Slavery wasn’t abolished in Britain and her empire by his government – nor was the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Pitt died a year before the slave trade was abolished. Baron William Grenville succeeded Pitt and was the Prime Minister when the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed on March 25th 1807.

Instead of abolishing slavery, Pitt decided to try to seize Saint-Domingue for Britain – it was after all, a very coveted possession. Less than a decade earlier it had been the most productive colony France ever had. Why wouldn’t Pitt covet it? But his greed cost Britain dear, culminating in a military disaster. Meanwhile, Toussaint got the offer he wanted – Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, the revolutionary French Governor of Saint-Domingue, as it then was, abolished slavery in 1793 and Toussaint abandoned his Spanish ‘allies’ and threw his lot in with revolutionary France. He now fought against his former allies and Britain too, as the revolutionaries switched sides.

Disaster

Pitt’s attempt to seize the French colony proved to be the worst military disaster in British history, costing huge resources, ships and men. It began in 1793 when France declared war on Britain and ended in September 1798 after the British had suffered debilitating losses to guerrilla warfare and Yellow Fever. It is hardly ever mentioned.

A force of 20000 men, mainly mercenaries, added to by 7000 slaves offered freed to to fight failed to make headway against the armies led by Toussaint Louverture and his equal among Mulattos, General André Rigaud. Two years before they ended the fiasco, Britain had accepted that they could not win, but carried on through fear of the effect on other nearby colonies. It remains a very costly military fiasco. The evacuation by the British coincided with Toussaint, then Colonial Governor, granting protection to colonists who had aided the British if they remained in Saint-Domingue. The disaster could have been even more costly.

The weather caused turbulent waters on route to Ireland and that wrecked French plans for Irish ‘independence’ by blowing supplies for Wolfe Tone’s rebellion off course – the same problems that almost scuppered William of Normandy’s invasion in 1066 and Julius Cæsar’s too. Pitt’s folly almost resulted in Ireland’s independence. It could have cost him even more dearly, and would have done too had it not been for an even greater folly committed by Napoléon Bonaparte.

War and More War

A year after Pitt abandoned hopes of seizing Saint-Domingue, two major events occurred. The uneasy alliance between blacks and Mulattos ended and Bonaparte’s coup brought Napoléon to power.

Rigaud and Louverture allowed their enemies to get inside their heads and turn them against each other – classic divide and rule. The former brothers-in-arms became bitter enemies, as the old racial suspicions resurfaced. The War of Knives ended in the siege of the southern port of Jacmel, which fell to Jean-Jacques Dessalines in March 1800. That led to the Mulatto leaders Rigaud, Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Pierre Boyer and the survivors of their army being evacuated to France. They would return in 1802, having been duped into a shameful plot.

The other event of 1799 was the end of the French Revolution. Napoléon seized power from the Thermidor government and set the world on a descent to war and tyranny. Saint-Domingue was a major part of his plans and so were the Mulatto leaders. They returned in 1802 under the command of Napoléon’s brother-in-law Charles Leclerc, but they had been tricked – the French invasion had no intention of including the Mulattos in a post-revolutionary government. They would be cowed into submission too by the fate of the revolutionaries.

Errors of Judgement

They thought that they were returning to govern Saint-Domingue and that the French government recognised that, but that was not Bonaparte’s intention at all. He planned to restore slavery – a plan approved of by Britain and the USA in advance of the invasion – and regain the most productive colony France had ever had. Toussaint, too, was misguided. He believed in France and in Napoléon and used the lull in hostilities to act against more radical revolutionaries.

It backfired against him, and almost against the revolutionaries. Among the casualties – executed on Toussaint’s orders – was the popular and courageous General Moïse, his own nephew. Moïse never trusted French colonial intentions and sided with former slaves keen to defend their gains against any who would re-enslave them, including the French. It led Moïse into what was considered a treacherous rebellion by Louverture. It was suppressed by Dessalines, who executed Moïse. Toussaint soon had cause to regret executing Moïse.